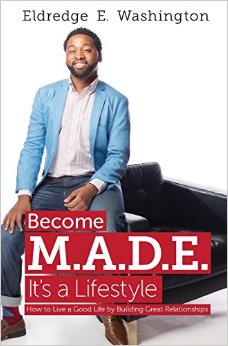

Among the many genres of literature that are available for public consumption perhaps the least appealing is the so-called “self-help” book. Often they adopt formulaic approaches to life’s most pressing challenges leaving readers completely unsatisfied and their innermost questions unanswered. Yet sometimes books appear in print that are written for the explicit purpose of edifying others and they manage to light a spark, not necessarily from the artistry of the written word alone but through the authenticity of the experiences reflected upon by the author. Eldredge E. Washington’s Become M.A.D.E. It’s a Lifestyle: How to Live a Good Life by Building Great Relationships delivers in this respect, which makes it an excellent primer for youth of any background seeking purpose or direction in a world where the costs of inaction are steadily rising. A self-described “hard-headed kid, who thought he was a thug because his pants were three sizes too big,” Washington takes the reader on a journey through his life as a Monroe native who moved to the heart of Atlanta and became infected by the hustling spirit that permeates the city. As he phrased it, “areas like Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead help me to stay on track and work hard … being around people who look like they are doing something productive makes me more productive.”

Among the many genres of literature that are available for public consumption perhaps the least appealing is the so-called “self-help” book. Often they adopt formulaic approaches to life’s most pressing challenges leaving readers completely unsatisfied and their innermost questions unanswered. Yet sometimes books appear in print that are written for the explicit purpose of edifying others and they manage to light a spark, not necessarily from the artistry of the written word alone but through the authenticity of the experiences reflected upon by the author. Eldredge E. Washington’s Become M.A.D.E. It’s a Lifestyle: How to Live a Good Life by Building Great Relationships delivers in this respect, which makes it an excellent primer for youth of any background seeking purpose or direction in a world where the costs of inaction are steadily rising. A self-described “hard-headed kid, who thought he was a thug because his pants were three sizes too big,” Washington takes the reader on a journey through his life as a Monroe native who moved to the heart of Atlanta and became infected by the hustling spirit that permeates the city. As he phrased it, “areas like Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead help me to stay on track and work hard … being around people who look like they are doing something productive makes me more productive.”

The theme of managing one’s environment is dominant throughout Become M.A.D.E. Barely beneath the surface in each chapter is a constant tug of war between the author’s efforts to remain psychologically centered and true to himself and ensuring that the people he surrounds himself with facilitate rather than impede this process of self-discovery. Consequently, Become M.A.D.E. acquires a dual function as part autobiographical snapshot and part Socratic dialogue. Several dialogues are taking place: between the author and his environment, the author and his family, and perhaps most significantly from a pedagogical perspective, the author and the reader.

Each chapter is framed by a series of questions, designed to stimulate introspection and a weighing of one’s priorities. Do you feel you need to create new relationships with people who support your dream? What do you normally do for fun with your friends? Name one mentor you feel you should model? Explain.

These queries serve as handy interludes which allow the reader to insert themselves as interlocutors in the conversation of self-development. Here we see another theme rise to the fore: the centrality of family and community as the foundation for one’s personal and professional development. Defying the capitalist myth of the “self-made man”, Eldredge overflows with appreciation when it comes to acknowledging the pivotal role that his parents, his sisters, and even some of his earliest employers played in helping him to achieve the level of success he has reached.

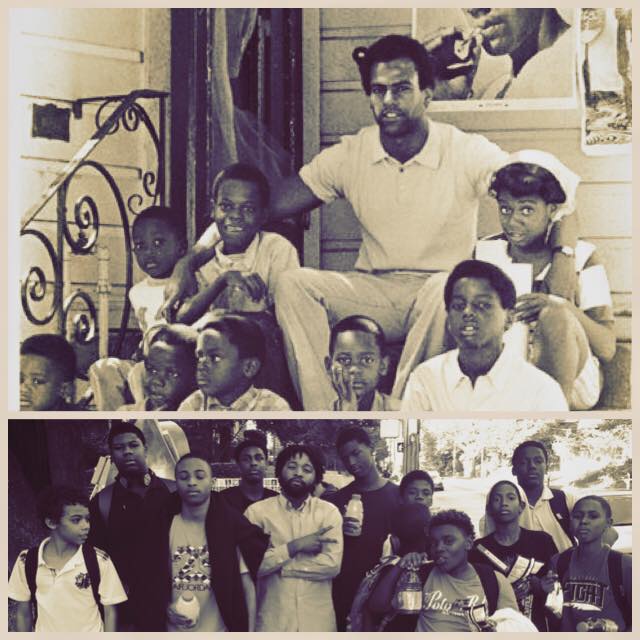

When his parents had to leave Georgia for a job opportunity Eldredge was tasked with the responsibility to exercise guardianship over his two younger sisters Winnie and Victoria. “In my head, I was their new daddy and in their head, I was the overprotective big brother who kept getting on their nerves,” he observed reflecting on the enormity of the challenge before him. Far from a choice, Washington embraced tasks of this kind as obligatory. Speaking on mentoring younger siblings he writes, “this relationship is sometimes overlooked … but the truth is that person is watching your every move and you are their mentor.” In fact, a careful reader may notice that Eldredge navigates roles from a mentor (with regard to being a guardian to his two younger sisters), to “peer” as it relates to the competitive relationship with his older sister Paula, to an “apprentice” (the third form of relationship) under his older brother Nick of who he admiringly writes, “where he went, I went; what he wore, I wore,” and eldest sister Shardia who “showed him that practice does make perfect and hard work will pay off in the end.” Indeed, a rich psychological portrait of the human self and its many permutations within the family unit is provided within these pages. Parts of it come off as a contemporary Anton Chekhov play.

In this regard, Eldredge resonates in the text as the archetypal dreamer who through a variety of human experiences becomes a revolutionary. Again, this component of the book could be more keenly perceived in the context of the author’s full story which is given partial, though in-depth, treatment here. Nonetheless, subtle indications of this revolutionary mindset appear near the end of the text where he memorably intones, “Your name is the only thing you will have when it’s all said and done, so make it stand for something when people mention you.” Such appeals to legacy building is a trademark feature in the writings of all revolutionaries whether it be Thomas Paine who wrote “We have the power to begin the world over again,” in his radical 18th century pamphlet Common Sense, Malcolm X’s prescient closing remarks in his autobiography that he had “cherished [his] ‘demagogue’ role,” under the knowledge that “societies have often killed the people who have helped to change these societies,” or Marcus Garvey’s fiery proclamation that “If I die in Atlanta my work shall then only begin, but I shall live, in the physical or spiritual to see the day of Africa’s glory.”

In this regard, Eldredge resonates in the text as the archetypal dreamer who through a variety of human experiences becomes a revolutionary. Again, this component of the book could be more keenly perceived in the context of the author’s full story which is given partial, though in-depth, treatment here. Nonetheless, subtle indications of this revolutionary mindset appear near the end of the text where he memorably intones, “Your name is the only thing you will have when it’s all said and done, so make it stand for something when people mention you.” Such appeals to legacy building is a trademark feature in the writings of all revolutionaries whether it be Thomas Paine who wrote “We have the power to begin the world over again,” in his radical 18th century pamphlet Common Sense, Malcolm X’s prescient closing remarks in his autobiography that he had “cherished [his] ‘demagogue’ role,” under the knowledge that “societies have often killed the people who have helped to change these societies,” or Marcus Garvey’s fiery proclamation that “If I die in Atlanta my work shall then only begin, but I shall live, in the physical or spiritual to see the day of Africa’s glory.”

Apart from the situation within his own family, it’s obvious by the end of the book that Eldredge has internalized this ethic of guardianship, an ethic he had to adopt at an unusually young age, and expanded it as a social doctrine to be implemented in our everyday lives and throughout the world. “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. may be the best example I can think of when it comes to starting a M.A.D.E. Generation. He discovered his purpose in life and he realized where he could help his generation.” The radical possibilities latent in this message cannot be overstated.

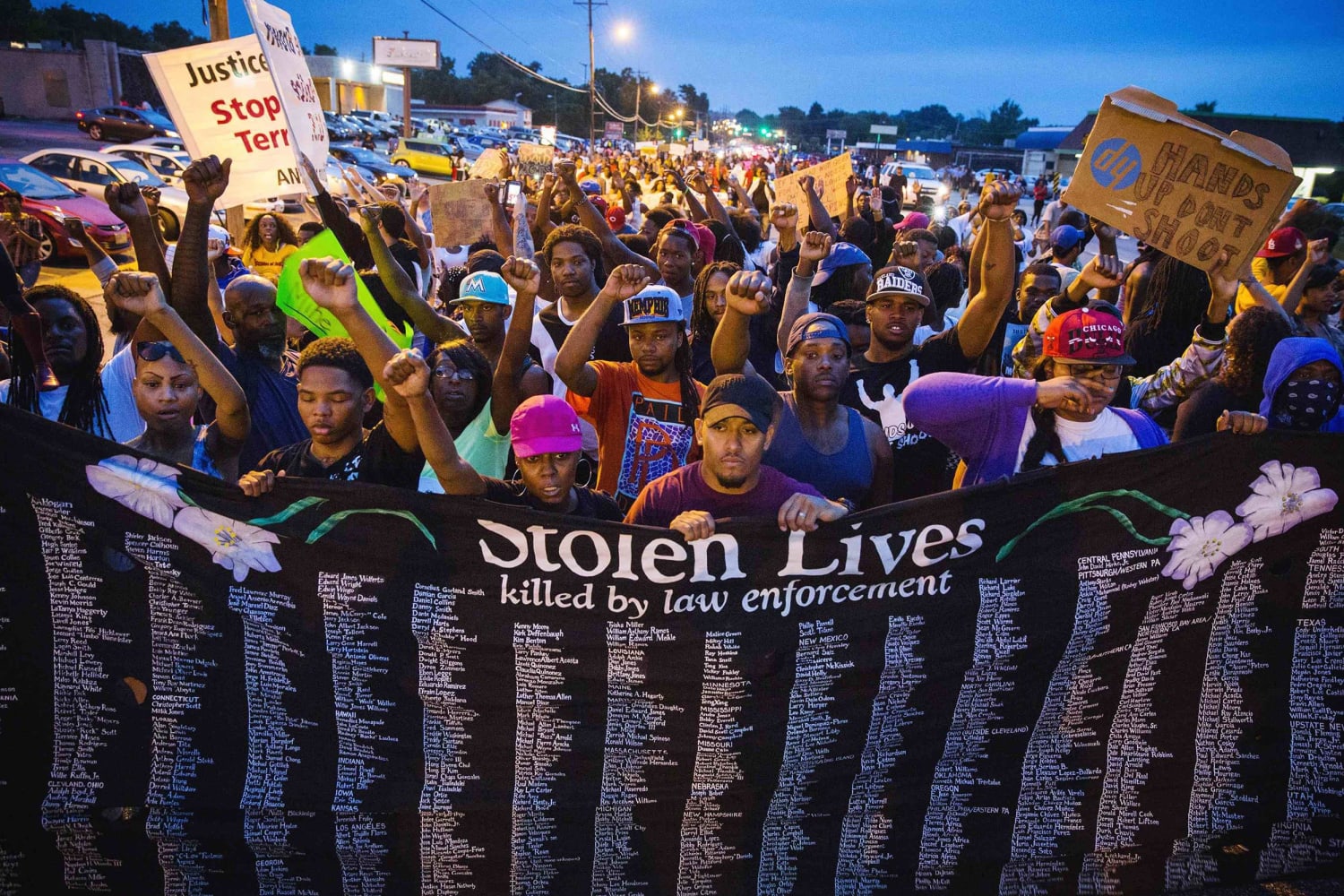

We currently live in a period where many of the civilizational traumas and evils that Dr. King faced loom large over any attempt toward self-determination or collective progress. #BlackLivesMatter has risen as the clarion call of a generation of youth discontent with the status quo and fully prepared to sever the generational chains that have bound them to lives of despair for far too long (the recent protest and removal of Mizzou University President Wolfe is a clear example of this). These cultural and political waves can only be sustained if we uplift and celebrate those who are not only willing to critically analyze the concentration of forces arrayed against the oppressed but leverage that analysis to constructively engage and undermine existing powers (if necessary to the point of collapse). However clearly it’s conveyed in the pages of his book, there can be no doubt that Eldredge Washington is among this number in the overlooked streets and alley ways of empire and for this reason Become M.A.D.E. is an essential read. A practical tool for liberation in the hands of Black youth and a valuable historical document for those who come after.