Few countries have endured as much violence and terror at the hands of imperial power as the island nation of Haiti. Liberated from French colonialism in 1804, the world’s first Black republic has become synonymous with the poverty and degradation that colonial powers have imposed on populations across the world. Nonetheless, these narratives often shield us from more humanizing portraits of Haiti that do not rely on stereotypes and clichés. Edwidge Danticat’s Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work provides such a portrait. From her commentary on the Haitian influences in the works of Basquiat to her account of the resilience of the Haitian people in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, Danticat’s writing leaves a lasting impression of an artist whose love of culture and ancestry is as vast as the waters which separate her from her native country. “Create dangerously for people who read dangerously. This is what I’ve always thought it meant to be a writer,” Danticat states in the opening chapter. This tension between the liberating potential of art and the oppressive power of dictatorship is a theme that emerges in several of Danticat’s essays.

Few countries have endured as much violence and terror at the hands of imperial power as the island nation of Haiti. Liberated from French colonialism in 1804, the world’s first Black republic has become synonymous with the poverty and degradation that colonial powers have imposed on populations across the world. Nonetheless, these narratives often shield us from more humanizing portraits of Haiti that do not rely on stereotypes and clichés. Edwidge Danticat’s Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work provides such a portrait. From her commentary on the Haitian influences in the works of Basquiat to her account of the resilience of the Haitian people in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, Danticat’s writing leaves a lasting impression of an artist whose love of culture and ancestry is as vast as the waters which separate her from her native country. “Create dangerously for people who read dangerously. This is what I’ve always thought it meant to be a writer,” Danticat states in the opening chapter. This tension between the liberating potential of art and the oppressive power of dictatorship is a theme that emerges in several of Danticat’s essays.

Reflecting on the execution of Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin, two guerilla fighters committed to the overthrow of the Duvalier dictatorship, Danticat provides the reader with a graphic example of the human costs of dissent. “After the executions of Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin … the young men and women of the Club de Bonne Humeur, along with the rest of Haiti, desperately needed art that would convince,” Danticat writes. “They needed art that could convince them that they would not die the same way Numa and Drouin did. They needed to be convinced that words could still be spoken, that stories could still be told and passed on.” Far beyond dead material for museums and libraries, Danticat portrays art as a living source of social and cultural uplift, a dialogue unfolding in history which finds its most potent expression in the collective memory of the Haitian people. Toussaint Louverture’s heroic battle against French colonists opens the door to this perspective and the subsequent resistance on the part of the “Great Powers” against any move toward total emancipation.

After all, “Haiti’s independence remained unrecognized by Thomas Jefferson … who [declared] its leaders ‘cannibals of the terrible republic.’” Echoes of this refusal to recognize the sovereignty of Haiti were likely heard in 1915 when US Marines invaded Haiti (beginning a 19 year occupation) and again during the two US-backed coups against the island’s first democratically elected President Jean Bertrand Aristide. Danticat zeroes in on these events as central to the cultural memory of Haitians and the artwork they produce. As Jean-Michel Basquiat commented in an interview with the New Art International, “Our cultural memory follows us everywhere, wherever you live.” Incidentally, Haitian influences figured prominently in the paintings of Basquiat. Untitled 82, To Repel Ghosts, and Toussaint L’Ouverture Versus Savonarola are just a few of the works Danticat cites as representative of this Haitian influence. “Haiti, like Puerto Rico and the continent of Africa, was obviously both in Basquiat’s consciousness and in his DNA,” Danitcat writes of the late artist, adding that the “arrow-wielding men” depicted in his paintings may represent the Haitian god of war Ogoun while one can see a “tribute to Baron Samedi and Erzulie [in] his heart-covered skulls and crosses.”

In addition to the theme of cultural memory, Danticat examines the climate of suspicion that burdens those forced into the margins of society. The devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina is given specific attention as an example of how the line between the citizen and those despised as the Other is blurred in moments of social crisis. “The poor and the outcast everywhere dwell within their own country … that’s why one can so easily become a refugee within one’s own borders.” Observations of this type mirror those made by other contemporary writers who have grappled with the complexities of exile. Late Palestinian American writer Edward Said is arguably the most noted scholar in this regard. In his 1993 study of colonial terror and its cultural consequences Culture and Imperialism he describes exile as “predicated on the existence of, love for, and a real bond for one’s native place.” For Said, “the universal truth of exile is not that one has lost that love or home, but that inherent in each is an unexpected, unwelcome loss.”

Danticat pays tribute to a number exiles in Create Dangerously. Above all she reveres Haitian author Marie Vieu-Chauvet. Much like Numas and Drouin, Marie Vieu-Chauvet is celebrated as a figure willing to defy the status quo in the face of overwhelming power. The intellectual kinship that Danticat feels toward Chauvet is clear throughout, most obviously in her remark that, “in Marie Vieu-Chauvet’s absence [she felt] orphaned.” Again, the ethical code of creating dangerously, which also entails “living fearlessly”, bounds the two artists across generational and geographic divides. As Danticat states in the opening chapter, “somewhere, if not now, then maybe years in the future, someone may risk his or her life to read us.”

Here one gets a clear impression of the significance of the reader in the creative process. In the production of subversive art Danticat seems to imply that both the writer and the reader enter into a tacit agreement whereby each is expected to courageously persevere in their defiance of authority for the sake of a broader social project. Instead of viewing art and revolutionary thought as operating in separate realms, as conventional wisdom demands, Danticat sheds light on the intersection between the artist and the revolutionary, alerting readers to the responsibilities artists must fulfill as agents of cultural change. In short, artists must practice “creating fearlessly … even when a great tempest is upon you.”

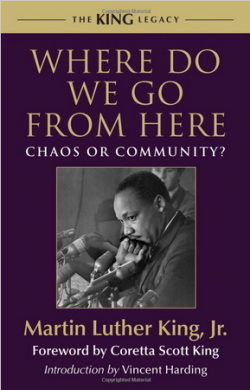

As witnesses to the repeated assaults on our common humanity and environment, Edwidge Danticat’s Create Dangerously couldn’t be a timelier read. Breaking violently with one-dimensional explanations of global affairs, Danticat’s commentary is a valuable contribution to a more informed discourse about those “on the other side of the water.” Furthermore, it offers paths forward so that citizens of the “first world” can begin their own initiatives to kill the silences that have long dominated the stories of their culture and dishonored the cultural memories of distant Others. Only when these lessons are absorbed can we begin to rise above the prejudices which inspired Jefferson’s denunciation of the “cannibals of the terrible republic,” and value the danger of art that nurtures our innermost desire for dignity and authentic self-determination.

If there ever were a manual designed to instruct colonial administrators on how to best manage an oppressed population there’s little doubt that one of its leading principles would be to repeatedly, and emphatically, portray every resort to violence, no matter how egregious, as an heroic attempt to promote peace. Such is the case with Israel’s long, brutal, and US-backed (crucial detail) occupation of Palestine. After the Palestinian Authority’s decision to seek membership in the International Criminal Court, what Newsweek described as Abbas “[rolling] the statehood dice”, US and Israeli officials wasted little time in venting their rage. While Israel reacted “by saying it will withhold $120 million of tax and customs receipts it collects on behalf of Palestinians each month” (a reality that flatly contradicts the Israeli self-image as a fortress of “democracy” and not a military occupier), the US State Department, in typical paternalistic fashion, condemned Palestinians for making a move that “badly damaged the atmosphere for peace.” Conversely, US military support for Israeli atrocities, a policy that made

If there ever were a manual designed to instruct colonial administrators on how to best manage an oppressed population there’s little doubt that one of its leading principles would be to repeatedly, and emphatically, portray every resort to violence, no matter how egregious, as an heroic attempt to promote peace. Such is the case with Israel’s long, brutal, and US-backed (crucial detail) occupation of Palestine. After the Palestinian Authority’s decision to seek membership in the International Criminal Court, what Newsweek described as Abbas “[rolling] the statehood dice”, US and Israeli officials wasted little time in venting their rage. While Israel reacted “by saying it will withhold $120 million of tax and customs receipts it collects on behalf of Palestinians each month” (a reality that flatly contradicts the Israeli self-image as a fortress of “democracy” and not a military occupier), the US State Department, in typical paternalistic fashion, condemned Palestinians for making a move that “badly damaged the atmosphere for peace.” Conversely, US military support for Israeli atrocities, a policy that made

In a society permeated with stereotypical portraits of Muslim communities intellectually honest narratives are regularly subordinated to sensational fairy tales replete with fear, xenophobia, and dehumanizing tropes purporting to explain violent behavior. Examples of this are too plentiful to enumerate. Dr. Omid Safi’s Memories of Muhammad chronicles the life of the Prophet Muhammad, the historical developments that characterized his time, and the various scholarly and theological interpretations that followed to provide an incredibly detailed description of Islamic teachings and the enormous influence they continue to exert today. In doing this Safi offers a much needed refutation to the monolithic conceptions of Islam that pervade US discourse. As Safi puts it, “If we are to understand the Islamic civilization that rightly sees itself as being shaped by the revelation given to Muhammad, it behooves us to engage the multiple ways in which Muslims have come to cultivate the memory of Muhammad.” Several realities must be factored into this analysis. Among these realities is the fact that “perhaps over 600,000 hadith reports came into circulation in the centuries after Muhammad’s passing” (“classical hadith scholars … accepted only 1 to 2 percent of the hadith in circulation as reliable”), that there is a rich tradition of devotional poetry uplifting the example of the Prophet Muhammad, and Muslim communities, from Sunni to Shia and Sufi, have brought their own unique interpretations to this body of work.

In a society permeated with stereotypical portraits of Muslim communities intellectually honest narratives are regularly subordinated to sensational fairy tales replete with fear, xenophobia, and dehumanizing tropes purporting to explain violent behavior. Examples of this are too plentiful to enumerate. Dr. Omid Safi’s Memories of Muhammad chronicles the life of the Prophet Muhammad, the historical developments that characterized his time, and the various scholarly and theological interpretations that followed to provide an incredibly detailed description of Islamic teachings and the enormous influence they continue to exert today. In doing this Safi offers a much needed refutation to the monolithic conceptions of Islam that pervade US discourse. As Safi puts it, “If we are to understand the Islamic civilization that rightly sees itself as being shaped by the revelation given to Muhammad, it behooves us to engage the multiple ways in which Muslims have come to cultivate the memory of Muhammad.” Several realities must be factored into this analysis. Among these realities is the fact that “perhaps over 600,000 hadith reports came into circulation in the centuries after Muhammad’s passing” (“classical hadith scholars … accepted only 1 to 2 percent of the hadith in circulation as reliable”), that there is a rich tradition of devotional poetry uplifting the example of the Prophet Muhammad, and Muslim communities, from Sunni to Shia and Sufi, have brought their own unique interpretations to this body of work. Whenever the US decides to bomb another country it is not uncommon to have that decision accompanied by debates about the efficacy of the bombing campaign, its stated pretexts, and its long term goals. Always underlying these displays of state violence is an unavoidable truth namely that these military attacks can only take place on the scale and frequency that they are occurring because the US is an imperial power and therefore feels entitled to behave as other imperial powers before it. Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism explores this unavoidable truth in many dimensions. Drawing from the wealth of cultural and literary traditions of France, Britain, and the United States, Said demonstrates how doctrines of colonial domination permeate nearly every aspect of life within metropolitan society.

Whenever the US decides to bomb another country it is not uncommon to have that decision accompanied by debates about the efficacy of the bombing campaign, its stated pretexts, and its long term goals. Always underlying these displays of state violence is an unavoidable truth namely that these military attacks can only take place on the scale and frequency that they are occurring because the US is an imperial power and therefore feels entitled to behave as other imperial powers before it. Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism explores this unavoidable truth in many dimensions. Drawing from the wealth of cultural and literary traditions of France, Britain, and the United States, Said demonstrates how doctrines of colonial domination permeate nearly every aspect of life within metropolitan society.