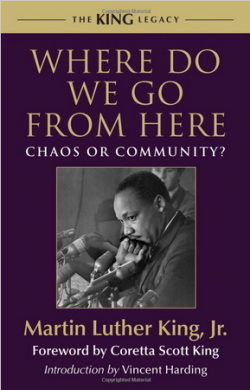

Conventional narratives terminate the Civil Rights Movement after the signing of the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965. The iconic photograph of President Lyndon Johnson signing the landmark piece of legislation as Dr. King admiringly watches on is portrayed as the culminating moment of many years of mass marches and civil disobedience. While the significance of this achievement should not be understated, this only offers a partial picture of the crises and challenges that defined Dr. King. Beneath all the fanfare of signing ceremonies and presidential speeches was a nation stubborn in its attachment to economic injustice, white supremacy, and imperial warfare. It is this post-1965 America that Dr. King confronts in his urgent appeal to a dramatically polarized society Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? “The paths of Negro-white unity that had been converging crossed at Selma, and like a giant X began to diverge,” observes King. This loss of support from white liberal allies, what King terms the “white backlash”, serves as a dominant theme in his writing and illustrates the necessity of a systemic, rather than piecemeal, critique of the status quo. Central to Dr. King’s indictment of the status quo is his condemnation of poverty, a plague as “cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism.” In an America indelibly altered by the emergence of mass based social justice movements like Occupy Wall Street King’s words resonate with a disturbing relevance. Furthermore, solutions were proposed to eradicate this “curse of poverty.” “Two conditions are indispensable if we are to ensure that the guaranteed income operates as a consistently progressive measure,” King insisted. “First, it must be pegged to the median income of society, not at the lowest levels of income … Second, the guaranteed income must be dynamic; it must automatically increase as the total social income grows.”

Conventional narratives terminate the Civil Rights Movement after the signing of the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965. The iconic photograph of President Lyndon Johnson signing the landmark piece of legislation as Dr. King admiringly watches on is portrayed as the culminating moment of many years of mass marches and civil disobedience. While the significance of this achievement should not be understated, this only offers a partial picture of the crises and challenges that defined Dr. King. Beneath all the fanfare of signing ceremonies and presidential speeches was a nation stubborn in its attachment to economic injustice, white supremacy, and imperial warfare. It is this post-1965 America that Dr. King confronts in his urgent appeal to a dramatically polarized society Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? “The paths of Negro-white unity that had been converging crossed at Selma, and like a giant X began to diverge,” observes King. This loss of support from white liberal allies, what King terms the “white backlash”, serves as a dominant theme in his writing and illustrates the necessity of a systemic, rather than piecemeal, critique of the status quo. Central to Dr. King’s indictment of the status quo is his condemnation of poverty, a plague as “cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism.” In an America indelibly altered by the emergence of mass based social justice movements like Occupy Wall Street King’s words resonate with a disturbing relevance. Furthermore, solutions were proposed to eradicate this “curse of poverty.” “Two conditions are indispensable if we are to ensure that the guaranteed income operates as a consistently progressive measure,” King insisted. “First, it must be pegged to the median income of society, not at the lowest levels of income … Second, the guaranteed income must be dynamic; it must automatically increase as the total social income grows.”

A brief look at contemporary America reveals an economic order passionately hostile to these prescriptions. Neoliberalism and its most committed enthusiasts in the business class have all but destroyed the possibility of a genuine social democracy. Foreshadowing the rise of this highly corporatized and anti-democratic organization of power King notes, “Automation is imperceptibly but inexorably producing dislocations, skimming off unskilled labor from the industrial labor force. The displaced are flowing into proliferating service occupations.” Faced with this exploitation King stressed the importance of unionized workplaces: “In days to come, organized labor will increase its importance in the destinies of Negroes.” As with the proposal for a guaranteed income, much work remains to be done in this domain.

Beyond the radical injustices of poverty in the US, King also directed his outrage abroad where America sent “black young men to burn Vietnamese with napalm, to slaughter men, women, and children …” The glaring contradiction within a country that “applauds nonviolence whenever Negroes face white people in the United States but then applauds violence and burning to death when these same Negroes are sent to the fields of Vietnam,” was indicative of a deeply rooted hypocrisy that permeated American life. “All of this represents a disappointment,” stated King. “It is disappointment with timid white moderates who feel that they can set a timetable for the Negro’s freedom.”

Similarly, Black men and women today are met with bitter condemnation in Ferguson and Baltimore. The burning of buildings and the shattering of store windows often arouses more outrage than the systematic murder of Black people at the hands of police officers or white vigilantes. And lest we imagine the immorality of the Vietnam War to be an artifact of history, it was not too long ago when America sent young men to burn Iraqis with white phosphorous, “to slaughter men, women, and children …” under the banner of “Western democracy.” In the occupied territories of Palestine such horrors also continue to unfold with Washington’s blessing. Furious denunciations could more productively be directed here.

Perhaps this is the most intriguing aspect about King’s writings. Even a surface reading of the text compels readers to engage critically with the world around them as it currently exists. Apart from ruminating on the contents of King’s famous “Dream”, Where Do We Go from Here inserts the reader squarely in King’s reality. In his description of the Black Power movement one can’t help but see many of the features it embodied echoed in the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s disregard for the politics of respectability, its forceful critique of white supremacy, its passionate demand that Black humanity be affirmed by a criminal justice system designed to dehumanize Black bodies are all points of contact between these two popular movements. Simultaneously attentive to the grievances of the Black Power movement as “a reaction to the failure of white power,” while critical of it as “a nihilistic philosophy born out the conviction that the Negro can’t win,”—“… that American society is so hopelessly corrupt and enmeshed in evil that there is no possibility of salvation from within”—King offers a nuanced perspective of what happens within oppressed populations when lofty promises by those in positions of power are crushed under the weight of venal self-interest and political calculation. “This gulf between the laws and their enforcement is one of the basic reasons why Black Power advocates express contempt for the legislative process.”

Closing this “gulf between the laws and their enforcement” is likely what compelled King to take up residence in Lawndale, Chicago, where “the problems of poverty and despair are graphically illustrated,” and “the phone rings daily with countless stories of man’s inhumanity to man …” Disturbed by the intensity of suffering, the “emotional and environmental deprivation” that surrounded him, King ominously added, “I understood anew the conditions which make of the ghetto an emotional pressure cooker.” Recall this is in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion of 1965, a social and political conflagration that “signaled the end of the monopoly previously held by advocates of nonviolence as a method of protest among blacks”, Ebony magazine’s description of the uprising in its 1971 Pictorial History of Black America. Indeed, the unfulfilled hopes of Selma and Montgomery birthed the righteous indignation of Watts.

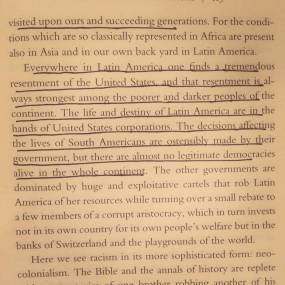

The King assassinated in 1968 was a King acutely aware of this sea change and the revolutionary potential that it held for America and the world at large. Political and economic elites are perfectly comfortable to erect monuments to a King conveniently reduced to idyllic visions of multi-racial and multi-religious harmony shorn of the particulars of authentic justice. More threatening is the King who observed “the cold hard facts today indicate that the hope of the people of color in the world may well rest on the American Negro and his ability to reform the structure of racist imperialism from within and thereby turn the technology and wealth of the West to the task of liberating the world from want.”

This is the same King who declared, according to his close colleague and author Vincent Harding, “something is wrong with the economic system of our nation … something is wrong with capitalism,” and “maybe America should move toward democratic socialism.” Washington cannot erect monuments to this King, principally because these views, and those who take the challenge they present seriously, continue to pose a grave threat to illegitimate authority wherever it brings down its oppressive boot. While the King imagined by power centers is immortalized in carefully chiseled statutes, the King of the oppressed was subversively mortal and many of his current celebrants would have much rather seen him in a morgue than on the DC mall. It is the spirit of this radical King that must be revived to guide us through the chaos of our current situation. The fate of future generations depends on it.

Source:

Ebony Pictorial History of Black America: Civil Rights Movement to Black Revolution. Vol. III. Chicago: Johnson Pub., 1971. Print.