No one remotely interested in US foreign policy can ignore the fact that massive civilian death has become an integral part of US warfare. Often termed “collateral damage”, these deaths are explained as the inevitable outcome of US hi-tech weaponry which often cannot discriminate between legal targets and innocent bystanders. Nonetheless, we can gain valuable insight into the reigning moral culture of certain societies by examining how powerful actors who wield these weapons respond to these deaths. Are the deaths acknowledged with remorse and sympathy or are they simply written off as the consequence of being “in the wrong place at the wrong time”? Sometimes the news cycle offers us case studies to test this question.

No one remotely interested in US foreign policy can ignore the fact that massive civilian death has become an integral part of US warfare. Often termed “collateral damage”, these deaths are explained as the inevitable outcome of US hi-tech weaponry which often cannot discriminate between legal targets and innocent bystanders. Nonetheless, we can gain valuable insight into the reigning moral culture of certain societies by examining how powerful actors who wield these weapons respond to these deaths. Are the deaths acknowledged with remorse and sympathy or are they simply written off as the consequence of being “in the wrong place at the wrong time”? Sometimes the news cycle offers us case studies to test this question.

Such a case study can be observed in the killing of two western hostages, Warren Weinstein and Giovanni Lo Porto. An American and an Italian, they were killed in a US drone strike targeting a “suspected Al Qaeda compound,” in Pakistan. As the Wall Street Journal reported “The incident also underscores the limits of U.S. intelligence and the risk of unintended consequences in executing a targeted killing program that human-rights groups say endangers civilians.” That drone strikes “endanger civilians” has been well documented for several years by reputable organizations like Reprieve and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Latest statistics reveal between 2,449 and 3,949 people have been killed in Pakistan since 2004. Of that figure between 421 and 960 were civilians (172-207 children killed). Yemen, Somalia, and Afghanistan are among the other countries targeted by drone strikes with the civilian death toll in Yemen between 65 and 96.

Unlike the tragic deaths of Weinstein and Lo Porto, none of these deaths elicited serious commentary within the US press beyond the predictable dismissal of unfortunate “collateral damage.” In fact, this indifference sometimes ventured into pure callousness. Take for example White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs’ response to the extrajudicial killing of Denver born teenager Abdulrahman Awlaki, a killing Attorney General Eric Holder rationalized on the grounds that he was “not specifically targeted.” After being asked by a reporter why this strike was authorized, Gibbs coldly replied that Abdulrahman “should have had a more responsible father,” a reference to Anwar Awlaki who was killed weeks before his son met the same fate. Needless to say, Gibbs would be ridiculed as a mindless sociopath if he expressed a similar sentiment in response to the deaths of Weinstein and Lo Porto, who, like Abdulrahman Awlaki, were not implicated in any crime. So the question is where does this indifference come from and, more importantly, what measures can be instituted to overcome it. Scholarship has plenty to say in this regard. MIT professor John Tirman explores this in his exhaustive study of civilian deaths The Death of Others. “The very fundamental norm of nation building and national survival as enabled by violence against savages,” Tirman observes, “is enormously consequential for how the deaths of the savages will be viewed.”

Further into the text Tirman adds:

“Correlating beliefs in a just world with beliefs in American ‘values’ is an essential addendum to understanding indifference … It is a foundation of American culture and has been from the beginning, and it powerfully shapes the attitudes and behavior of Americans from childhood. In its sheer explanatory power for the ‘American experience,’ it really has no rivals. It is an account of the entire scope of European immigration, expansion, and subjugation of the indigenous tribes, class conflict, and finally, American globalism.”

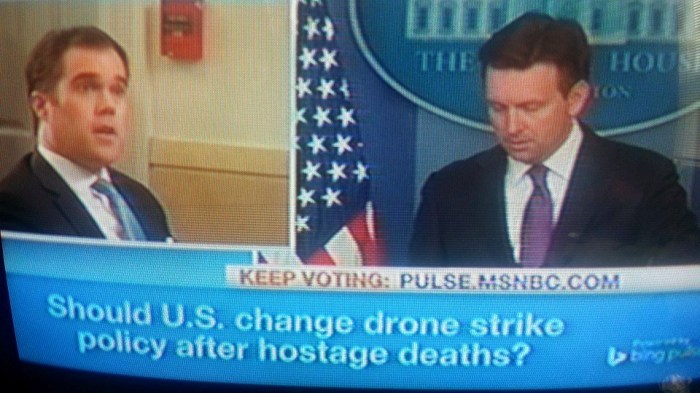

Therefore, engaging with the roots of American indifference to the deaths of others entails far more than merely becoming more “sensitive” to civilian suffering but a much more fundamental reevaluation in our complicity in crimes against humanity and what we can do to terminate these crimes given our ability to influence state policy. Recent polling illustrates that such an engagement has been severely lacking. Global polls published by Pew Research reveal the US as an international outlier in their support for drone strikes. Opposition in other countries is not only held by majorities but overwhelming majorities. In Lo Porto’s native Italy only 18% of its citizens supported drone strikes.  Nevertheless, US public opinion has remained relatively stable in the face of these enormous costs to civilian populations abroad. It was only after the deaths of these two western hostages that MSNBC raised the question if US drone policy should be changed. If one believes in an afterlife, there were no doubt hundreds of Yemeni, Pakistani, and Somalian ghosts asking themselves why this question could not be raised after their deaths. The huge role that pure racism plays in entrenching popular indifference to non-western victims of drone strikes cannot be ignored. In Tirman’s words, “because of the long history of racism in America, its powerful political effects over the whole of American history, and its insinuation into U.S. expansion, its plausibility as the base of indifference is apparent.”

Nevertheless, US public opinion has remained relatively stable in the face of these enormous costs to civilian populations abroad. It was only after the deaths of these two western hostages that MSNBC raised the question if US drone policy should be changed. If one believes in an afterlife, there were no doubt hundreds of Yemeni, Pakistani, and Somalian ghosts asking themselves why this question could not be raised after their deaths. The huge role that pure racism plays in entrenching popular indifference to non-western victims of drone strikes cannot be ignored. In Tirman’s words, “because of the long history of racism in America, its powerful political effects over the whole of American history, and its insinuation into U.S. expansion, its plausibility as the base of indifference is apparent.”

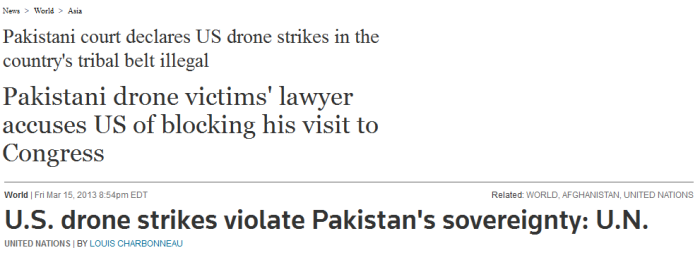

Further insight how racism serves as “the base of indifference” can be deciphered in the rules of engagement surrounding the Obama administration’s drone policy. In all the commentary that has flooded newspapers and television programs about these tragic killings, not one person has thought to ask what right the US has to bomb Pakistan in the first place. Legal questions of this kind are inconceivable. Instead we are subjected to presidential platitudes about the unintended outcomes inherent in the “fog of war.” Incidentally, this question about the legality of drone strikes is alive and well outside of circles of US power.  Not only has the Pakistani High Court in Peshawar condemned drone strikes as an act of aggression but UN official Ben Emerson has raised many, albeit mild, criticisms of the Obama administration’s drone program, particularly what he described as “a violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty.” When Pakistani lawyer Shahzad Akbar attempted to enter the US to testify about drone strikes his entry was blocked. “Before I started drone investigations I never had an issue with US visa. In fact, I had a US diplomatic visa for two years,” Akbar remarked when interviewed by the UK Guardian. None of these valiant efforts to shed light on the US drone program influenced US policy makers or public opinion in the slightest regard nor were there any polls on MSNBC (as there have been since the killing of the two western hostages) asking viewers to go online and vote if drone policy should be rethought.

Not only has the Pakistani High Court in Peshawar condemned drone strikes as an act of aggression but UN official Ben Emerson has raised many, albeit mild, criticisms of the Obama administration’s drone program, particularly what he described as “a violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty.” When Pakistani lawyer Shahzad Akbar attempted to enter the US to testify about drone strikes his entry was blocked. “Before I started drone investigations I never had an issue with US visa. In fact, I had a US diplomatic visa for two years,” Akbar remarked when interviewed by the UK Guardian. None of these valiant efforts to shed light on the US drone program influenced US policy makers or public opinion in the slightest regard nor were there any polls on MSNBC (as there have been since the killing of the two western hostages) asking viewers to go online and vote if drone policy should be rethought.

There’s plenty more that could be said about the illegality and blatant immorality of a program world-renowned political dissident Noam Chomsky has described as “the most extreme terrorist campaign of modern times”, but these insights should suffice in exposing the glaring double standard that drives media discourse about drones and, by association, the hideous policies that increase civilian casualties outside the gaze of public scrutiny. Perhaps if the people of Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Somalia could magically evolve into blonde haired, blue-eyed white people this conversation would have emerged earlier. It’s utterly disgraceful that it took the tragic deaths of two western aid workers for it to finally begin but that doesn’t diminish the significance of the fact that this conversation has begun and that’s a promising start for all genuinely concerned about human life both in the “west” and abroad.

Sources:

The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America’s Wars by John Tirman

http://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/category/projects/drones/drones-graphs/

http://www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/52/

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/16/us-un-drones-idUSBRE92E0Y320130316

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/24/us-accused-drone-hearing-lawyer-visa-pakistan

Hatred and discrimination against marginalized communities is a standard feature of imperial societies. From the history of institutionalized oppression endured by Black people under the US criminal “justice” system to the tide of racism faced by Latinos through unjust immigration laws (re: Arizona), those without institutional power are recognized primarily as threats to be contained, silenced, or liquidated. Among these maligned communities are Muslims. Routinely stereotyped as either “terrorists” or “terrorist sympathizers”, Muslims have been made the focus of a climate of fear has been forged by corporate and State power. This demonization has reached an ugly peak since the attacks on 9/11. Muslims are separated into moral categories of “good” and “bad”, “good” Muslims being those who accept the objectives of US domination and “bad” Muslims being those who resist.

Hatred and discrimination against marginalized communities is a standard feature of imperial societies. From the history of institutionalized oppression endured by Black people under the US criminal “justice” system to the tide of racism faced by Latinos through unjust immigration laws (re: Arizona), those without institutional power are recognized primarily as threats to be contained, silenced, or liquidated. Among these maligned communities are Muslims. Routinely stereotyped as either “terrorists” or “terrorist sympathizers”, Muslims have been made the focus of a climate of fear has been forged by corporate and State power. This demonization has reached an ugly peak since the attacks on 9/11. Muslims are separated into moral categories of “good” and “bad”, “good” Muslims being those who accept the objectives of US domination and “bad” Muslims being those who resist.