Anyone seeking to gain an understanding of the dominant moral culture of America’s intellectual class could learn a great deal by studying how they address the crimes of other states versus those of their own. The 20th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide just passed and prominent newspapers commemorated this atrocity with numerous op-eds and articles detailing the nightmarish horrors of those days. The New York Times editorial board remembered the killings as the day “the world stood by and let the blood bath happen.” In an effort to deal with the “unanswered questions” of the massacres the board urged France to “open its records to public examination.” It was necessary for the French to do this because they had “close relations to the Hutu-dominated government that planned and incited the genocide.” “Addressing the poisonous legacies of Rwanda’s genocide,” the board continued “is the only way to avert future tragedy,” and “the best way to honor Rwanda’s dead.” Here we can discern a clear principle, namely that governments which maintain “close relations” with genocidal regimes have a moral, if not legal, responsibility to disclose their internal records. This clear principle was not to be found in a May 15 Times editorial titled Unsolved Atrocities in Bangladesh. Instead of calling for Washington to “open its records to public examination” for the Nixon administration’s “close relations” with the genocidal regime in West Pakistan the board harshly condemned Bangladesh’s war crimes tribunal for “harming its own credibility,” and displaying a “contempt for international standards of justice [that] appears to know no bounds.”

Anyone seeking to gain an understanding of the dominant moral culture of America’s intellectual class could learn a great deal by studying how they address the crimes of other states versus those of their own. The 20th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide just passed and prominent newspapers commemorated this atrocity with numerous op-eds and articles detailing the nightmarish horrors of those days. The New York Times editorial board remembered the killings as the day “the world stood by and let the blood bath happen.” In an effort to deal with the “unanswered questions” of the massacres the board urged France to “open its records to public examination.” It was necessary for the French to do this because they had “close relations to the Hutu-dominated government that planned and incited the genocide.” “Addressing the poisonous legacies of Rwanda’s genocide,” the board continued “is the only way to avert future tragedy,” and “the best way to honor Rwanda’s dead.” Here we can discern a clear principle, namely that governments which maintain “close relations” with genocidal regimes have a moral, if not legal, responsibility to disclose their internal records. This clear principle was not to be found in a May 15 Times editorial titled Unsolved Atrocities in Bangladesh. Instead of calling for Washington to “open its records to public examination” for the Nixon administration’s “close relations” with the genocidal regime in West Pakistan the board harshly condemned Bangladesh’s war crimes tribunal for “harming its own credibility,” and displaying a “contempt for international standards of justice [that] appears to know no bounds.”

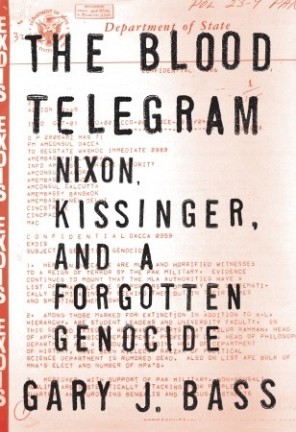

Amazingly, no one on the Times editorial board could see the irony of a paper that uncritically and aggressively circulated Bush administration lies in the run up to the Iraq war lecturing Bangladesh–a country that has never invaded anyone–about “international standards of justice.” Furthermore, there was no commentary on just how deep and unabiding the US role was in what the board calls the “horrific crimes committed during the country’s struggle for independence.” More than “horrific crimes”, Pakistan’s military assault on Bangladesh was, by any rational standard of international law, a genocide. Drawing from a vast documentary record of White House tapes, phone conversations, interviews and internal documents Gary J. Bass’ The Blood Telegram recounts this US-sponsored bloodbath in graphic detail. Conventional narratives portray the mass slaughters in Bangladesh as the gruesome byproduct of the India-Pakistan conflict with the US, at worst, “tilting” toward Pakistan. In reality, the US enthusiastically embraced the military dictatorship of Yahya Khan throughout, providing him with crucial military and ideological support to carry out the massacres. Yahya was, in the words of President Nixon, “a decent man.”

Prior to the onset of the killings East Bengal’s Mujibir Rahman won Pakistan’s first democratic election in a landslide victory (Mujibir’s Awami League won 167 out of 169 seats). All credible observers deemed the elections to be “free and fair.” The Nixon administration, firmly committed to a unified Pakistan and opposed to East Bengali autonomy, refused to recognize the outcome. Much like the Haitian election of Aristide and the Palestinian election of Hamas, the population of East Bengal voted “the wrong way,” in a free election. Yahya responded to this crime of democratic participation by shutting down the National Assembly, eliciting widespread protests throughout the east. Presented with the likely consequence of a killing spree the Nixon White House, at the insistence of Henry Kissinger, opted for a policy of “massive inaction.” Though the State Dept. warned of “a real blood-bath … comparable to the Biafra situation,” Nixon persisted in his support of Yahya, later qualifying his decision by saying “I didn’t like shooting starving Biafrans either.”

As the murders escalated, the Nixon administration worked vigorously to silence any critics within the State Dept. After US Consul General in Dhaka Archer Blood transmitted a telegram condemning Washington for its “moral bankruptcy” Kissinger derided him as that “maniac in Dacca.” Unlike the “realists” on Pennsylvania Avenue, Blood was “regarded as being squishy. Maybe a little too enamored with the Bengalis,” and “a little-soft headed” (words of White House Staffer Samuel Hokinson). For this act of dissent Blood was fired. Meanwhile, the Nixon administration continued to pour arms into Pakistan, even violating a US arms embargo, enlisting the Shah’s Iran and Jordan to provide Pakistan with jet bombers, an act acknowledged to be criminal in internal discussions. When the killing subsided, the civilian death toll reached conservative estimates of 300,000. Other credible estimates place the toll at one million dead. Reviewing the success of this campaign against dissent, Henry Kissinger exhaled “No one can bleed anymore about the dying Bengalis.”

Among those bleeding over “dying Bengalis” was the Indian army. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi supported the independence struggle of East Bengal, first through arming and training a guerilla insurgency, the Mukti Bahini, then through a military invasion on December 3, 1971. When Indian troops began bombing Pakistan the White House erupted in hysterics. Kissinger called the Indian invasion the “rape of an ally”, an act of unprovoked aggression. Not only did this characterization overlook the fact that Pakistan bombed India’s airfields in Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh prior to the Indian attack but when Kissinger made this statement the US was participating in an actual act of military aggression in its terrorist war against the people of Indochina. Inconvenient realities of this kind did not interfere with the Nixon administration’s policy of treating the genocide as a purely “internal matter” between the western and eastern regions of Pakistan. Washington’s subversion of the 1970 elections and arming of the military dictatorship as it carried out mass murder was not deemed interference in an “internal matter.” This was an attempt to prevent Bangladesh from becoming, in Kissinger’s words, “a ripe field for Communist infiltration.” On the other hand, capitalist “infiltration” was perfectly legitimate, even at the cost of over 300,000 lives.

And the human costs could have been significantly worse. In a shockingly disproportionate show of force, Nixon sent a nuclear aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise, into the Bay of Bengal. The purpose of this “atomic-powered bluff” was to coerce India into abandoning its military campaign in Pakistan. When the American press sought Kissinger’s reaction to Indians outraged by this brazen threat he replied “What the Indians are mad at is irrelevant.” Suppose in the middle of the Cuban Missile Crisis Nikita Khrushchev responded to American fears of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba by saying “What the Americans are mad at is irrelevant.” Would this response elude historical memory as easily as Kissinger’s remark? Incidentally, Khrushchev would be more justified in making such a statement since he wasn’t putting nuclear missiles in Cuba to abet a genocidal campaign in Havana. The threat of nuclear war was also narrowly averted when the Chinese decided not to mobilize its forces on India’s borders. Kissinger requested that the Chinese send troops to India’s borders to deliver a message that their intervention in Pakistan was intolerable. Despite this grave danger to humanity “Kissinger still insisted on backing China in a spiraling crisis.” Kissinger felt it was necessary to cooperate with China in order to lay the groundwork for Nixon’s famous visit to China in 1972. The fact that hundreds of thousands of Bengalis had to die in the process mattered little to his strategic calculus. Well aware of the risk this policy entailed, Nixon put it in “Armageddon terms”, saying “the Chinese move and the Soviets threaten and then we start lobbing nuclear weapons.”

Buried beneath the Cold War politics and superpower maneuvering that dominates discussions in educated circles, Bass places the mass killings in Bangladesh’s war of liberation in proper historical context. Bangladesh, he notes, “ought to rank with Vietnam and Cambodia among the darkest incidents in Nixon’s presidency and the entire Cold War.” Surely, in a society free from ideological restraints that hail war criminals as foreign policy gurus this would be the norm. Two years after the 1971 genocide “a Gallup poll found that [Henry Kissinger] was the most admired person in the United States.” In May 2013 the University of Bonn honored Kissinger with a professorship for international relations and international law, describing him as “one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century and a brilliant scholar.” One can easily imagine the hundreds of thousands of Bengali civilians killed by US arms under the Yahya dictatorship struggling to see the “brilliance” in orchestrating the murder of hundreds of thousands of innocent men, women and children. Predicting the public response to his administration’s backing of Yahya, Nixon stated that “people don’t give a shit whether we’re to blame–not to blame–because they don’t care if the whole goddamn thing goes down the cesspool.” This statement reverberates in the omissions of the New York Times , award ceremonies for war criminals and other illustrations of historical amnesia that make the atrocities in East Bengal a “forgotten genocide”; forgettable to the aggressors, evidence of our “contempt for international standards of justice” to the victims.

Sources:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/09/opinion/after-rwandas-genocide.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/16/opinion/unsolved-atrocities-in-bangladesh.html

http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/EN/Infoservice/Presse/Meldungen/2013/130526_Kissinger_Professur.html